(or Is the Architecture still a Fine Art?)

It appears nowadays that people no longer see architecture as a visual art form. Instead, it is often placed under the engineering category. Obviously, “something is rotten in the state of Denmark”. Strictly speaking, the term “fine art” signifies a man-made aesthetically charged form. From this perspective, therefore, any kind of design, whether graphic, industrial or architectural, is a fine art, or at least contains a weighty component of this field.

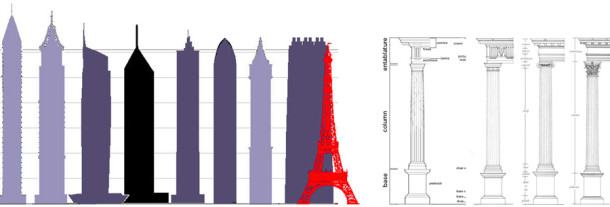

Viewed in this context, architecture has not just been a fine art — I argue it is one of the most important and the most complicated of all fine arts. The massive, all-controlling scale of the finished works and numerous factors complicate the task, and contribute to this designation. Included are serious functional, economic and structural considerations, a complex of regulating rules and, finally, the client’s vision and demands. With these circumstances in mind, it is a challenging, even daunting, task to achieve a perfect solution. Moreover, of the three Vitruvian virtues — utility, solidity, and beauty (utilitas, firmitas, venustas), in most cases, we appreciate many architectural objects only by their visual appeal—their ”beauty”. While walking in a city street or passing a group of buildings while driving, one cannot judge as to how comfortable those building actually are in terms of function or how economical and solid they are, yet their appearance, without fail, affects the environment, and therefore one’s mood.

The creation of a picture, fashion style, or all manner of accessories usually takes a number of studies where the artist hones the esthetic aspect of the future project. In architecture however, this detailed development often applies to functional and structural components only, while the visual component is totally subjugated to the former two and is often limited to purely decorative detailing of the resulting form. Well, this is a legitimate approach as well, but, regrettably, the result is not always satisfactory. Also, while we can always replace an old picture on the wall or a desk lamp, or discard clothes that are no longer in fashion, there is no way out from the ubiquitous architectural aesthetics.

I’d like to stress the fact that it is not just a created visual form that the term “fine art” defines, but rather the ancient art of beauty, with its rules and laws. Taking all of the above, as well as the enormity of scale, into account, it’s not enough to rely on the architect’s perfect esthetic taste or rich, and canon-free, imagination. Professional methods of form development are of paramount importance. It takes years, as we all know, to become a professional artist or illustrator, industrial or fashion designer – years of studying the laws and secrets of the craft. Modern architects, on the other hand, unlike their old-school predecessors, have shifted away from the fine arts toward new technologies, new approaches and revolutionary solutions in the environmental field and other aggregate aspects of modernity. They also have had little chance to study art in detail: So many new subjects are now covered in architectural curriculum that in many cases an architect’s exposure to art may be limited to an art club in high school and a couple of basic drawing classes at college.

Indeed, the body of architecture today is very complex, with many different industries involved. The architect or “Master Builder” acts an orchestra conductor, creating a frozen music and managing a large orchestra which includes HVAC specialists and electricians, construction engineers, acoustic specialists and lighting designers. Someone works on details, one concentrates on solving functional problems, often a separate group of experts on finishing and interior decoration.

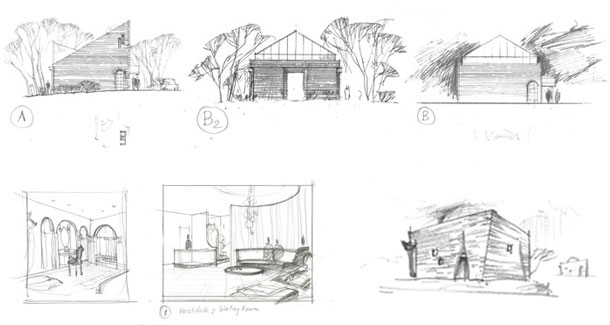

Is it not obvious that the question of styling and shape itself is no less difficult and no less important, to not have a team member, who would help specializing in matters of visual composition. Isn’t it obvious that the method of creating forms, from sketch to sketch, from the first visualization to a completed rendering is a versatile tool and works the same for creating garments, industrial design objects, small piece of jewelry, and the huge scale building with its contexts and peculiarities.

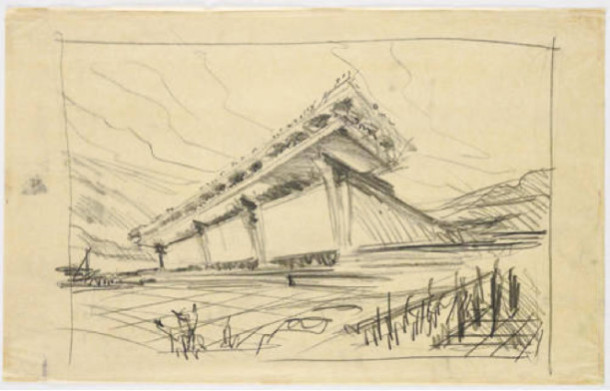

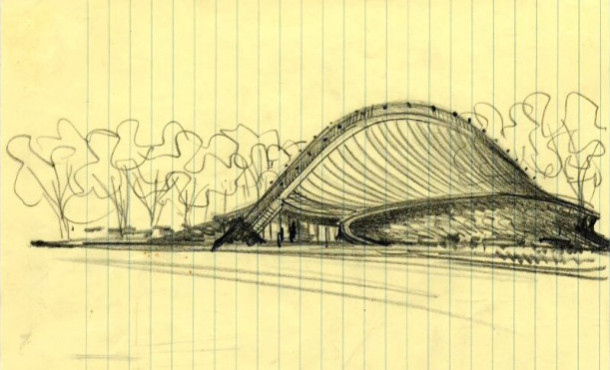

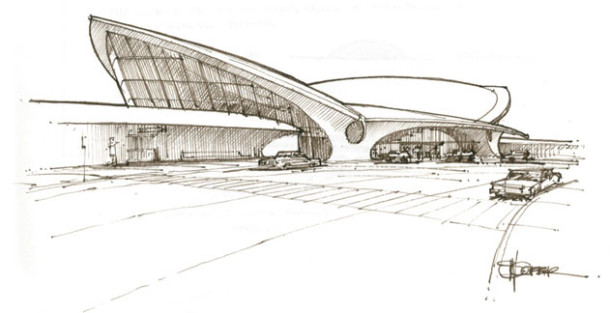

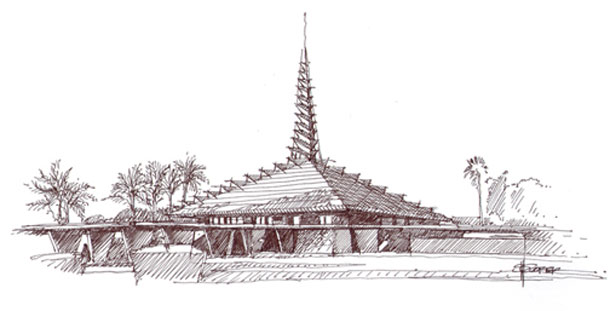

It is becoming clear that the architectural team should include a visual artist in addition to members specializing in a variety of other fields. The role of a visual artist shall not be limited to the Extrude button that raises up the developed and balanced functional plan in 3D imaging. He takes a pencil, and the artist’s hand, led by instinct, begins to draw lines and strokes to be eventually transformed into definitive architectural forms, specific materials, ledges and slopes, accents and the background.

Michael Graves makes this same case in his NYT article called Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing: “…Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets. Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design…” (Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing)

Can we imagine the buildings designed by Saarinen, Frank Gehry, Calatrava or Zaha Hadid as completed architectural plans automatically extruded to 3d? Is it possible that Frank Lloyd Wright, Ernest Flagg or Cass Gilbert, or aforementioned Michael Graves first saw images of their creations only days before being presented to the client? Rather, they worked on the visual form from the very first days, while other project components, as mentioned above, were simultaneously addressed.

Architectural rendering is not just the visualization of hard-to-read plans, facades and reserves. Nor is it just a tool for successful presentation and promotion. Rather, it is an integral part of the very design process at its every stage, from the day the creative idea is formulated to the day the newly-built space receives its first visitors and begins an independent life of its own. It is a path to the result that will leave no place for the question if our architecture is indeed a fine art.

Illustrations:

1. In reference to mastery of the language of fine arts: Adolf Loos,

Chicago Tribune competition,1922 (a contemporary 3D model).

Apart from many other things, the building is a witty expression of

the immortality of architectural esthetic values. This half-joking

and half-serious anticipation of things to come has been confirmed

in many future projects. It outlines a formula, as it were, that will

be followed, intuitively or otherwise, by the authors of many

famous sky-scrapers. When the project was rejected by jury Loos

proclaimed: “If not in Chicago, in any other city. If not for the

Chicago Tribune, for any other entity. If not by me, by any other

architect.”

It develops the building corner as the principal accent. The spirit of Time Square dictates a certain unpredictable irrationality which is typical of its general deconstructivism. This is one of the first sketches that aims at marking major milestones for further development (author’s drawing).

It is great to know that rendering is an important part of the very design process at every stage. I would imagine that any designer would want to produce quality results for their clients. I think they should look for a reliable company that can provide VRay products and training courses with competitive pricing.

Rotometrics